- Home

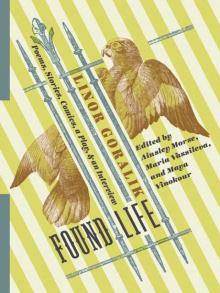

- Linor Goralik

Found Life Page 3

Found Life Read online

Page 3

—…during the war. He made it all the way to Berlin and sent her a package from the front, with some children’s things for Mama and Pasha, tablecloths, some other stuff, and this gorgeous negligee. I mean, no one here had seen anything like it, you know what I mean? She unwraps it—and there’s a noodle stuck to it. As if the woman had been eating and accidentally dropped one. She threw up for twenty minutes, then she packed up the kids and that was it. He spent half a year looking for her afterwards.

—…two whole weeks before I menstruate my breasts hurt so bad that even walking is hard, every step hurts. And it’s like that e-ve-ry month! And that’s before I menstruate! And during I just want to howl all the time, but I have to go to work. And just survive. Forget about it! It’s just awful. And then if you think about it, the worst is yet to come. There’s still, you know. Try to get pregnant eight times, actually go into labor twice. And I bet one of those will be a C-section. Jesus God. Then get your tubes or your ovaries removed or some other thing. Not to mention menopause. And uterine cancer! Lordy, sweet Jesus, I just don’t want to be a girl, I just don’t want to, I don’t. The one good thing is at least I lost my virginity. At least that’s done, thank God.

—…from the cemetery, and that’s when she started smoking again, my nerves are shot to hell too, and I should have just left her alone on a day like that but I just freaked out. She hadn’t smoked since her first pregnancy. And I walked right up to her from behind and tore the cigarette out of her mouth, and she turns toward me so slowly, and she’s got this expression on her face and I know: she’s just going to deck me right here and now. She’d had a bit to drink there at the cemetery, too, and I’m standing there thinking: all right, come on, bring on the hysterics—because, well, I just felt so bad for her…And she’s looking at me, you know, scowling, and she says slowly: “And now, Volodya, we’re going to play daddy and mommy.” I just look at her, and she says: “Daddy and mommy. You’ll be my daddy now, and I’ll be your mommy.”

—…whenever his mom isn’t around he’s like this tender lover.

—…I grabbed Lena by the hand and we ran to the neighbors’. And it’s like that once a week now, he gets plastered and just goes after her, paws out, you know, lunging like a backhoe. We’ve already got it down: jump into your boots and off we go. But otherwise, Natasha, I really can’t complain. Everyone always said: no guy’s ever going to love someone else’s kid, well, go figure.

—…so I’m walking along and all of a sudden I feel someone looking at me. I had that coat on, the black-and-white checked one, back then it was the latest thing, Inka managed to get it for me, two months’ salary. So I’m walking downhill on the side of the street where, you know, there’s like an art salon or Art House, what was it? You know, where the Indian restaurant is now. And I can just feel that someone’s watching me, you know? Well, so I kind of carefully turn my head, and there on the other side there’s this young man and he’s, you know, not even hiding it. And there’s something about him…he looks somehow…maybe he looked like some famous actor…But I just, you know, just right then I realized: well, that’s it, that’s my future husband. I mean, do you believe in this sort of thing? I looked at him for just a second and just knew everything. So I’m going along all proud, towards Neglinnaya, but my heart’s going boom-boom, boom-boom, boom-boom. I sneaked a peek and saw that he’s, like, walking on the diagonal, like towards the edge of the sidewalk. And I realize that we’re going to meet right there on the corner. And I don’t even think about what I’ll say ’cause it’s like I get it already, you know? Like I get it without anything being said. And I’m just walking and thinking: I could have gone to pick up those heels first, and that would have been it! And I can’t think about anything else, except that I might have gone to pick up those stupid pumps and then I would have never met my husband! And I peek over again—and he’s already stepping off the sidewalk and even speeding up, you know, to intercept me. And right then, like right there a car backs out—like, screeeeeeee!!! Literally, I mean literally an inch away from him. Like really less than an inch. I’m standing there, I mean, my heart stopped. I can’t move a muscle. And he’s standing there like a statue. And you know, he turns around—and heads back onto the sidewalk, and starts trotting up the stairs to, like, the subway…And I’m just standing there thinking: I bet my pumps aren’t even ready yet.

—…and until the dog kicks off he won’t move out of that apartment.

—…taught myself, so my brain just turns off at moments like that. I’m a robot. I could tell a block away from the smell that it was fucked over there. I was right—there was nothing left of the café, just a single wall. That’s when I just flip the switch in my head: tick-tack. I’m a robot, I’m a robot. Then for three hours we, you know. We generally break up into groups of three, two do the collecting and one closes up the bags, so there I am zipping—zhzhik, and it’s like these weren’t people, we’re just collecting various objects and putting them in sacks. We were in four groups, finished in three hours. Zvi says to me: let’s do one last walk-through, just in case. Sure, what do I care—I’m a robot. We walk around, look in the corners, the wreckage, where we can we rummage around a little. Looks like we got everything. And then I notice, like out of the corner of my eye, some kind of movement. And I’m like: “What’s that?” I look, and by the one wall that didn’t collapse, there’s a display case, still in one piece, and there’s pastries in it, rotating. And that’s when I threw up.

—…how old is he? Probably pushing fifty. Gray hair, I always loved that type. You know, he did ballet as a kid, then worked for the KGB, so, like, basically a real inspired dude.

—…forgot it on the desk. I put the pencil case in my schoolbag, and the, uh, folder, but I left the notebook. So at recess I see it’s not there. I got a clean notebook from Masha, I’m like: “Masha, give me one of those, you know, a notebook,” so I start writing out the homework, but didn’t have enough time. So she’s like: “Give me the notebook,” but it’s only half-done. So she’s like: “That’s it, you get a C, I’m calling your father in tomorrow morning.” I’m walking home all…thinking: man, that’s it. ’Cause I never had any Cs before, he’s going to really bawl me out! Well, he wasn’t home, still at work, and I’m sitting there waiting for him, it’s almost dark out, like seven o’clock. And I think, well, I’ll go outside so I can tell him right away when he gets home. And it was raining, well, like just a little. So I went out. I took Chapa and we went out. I’m standing there all wet already and I see my father coming. Chapa ran up to him and I go too and say right away: “My notebook, I forgot it, and, uh…At recess I started on a new one, but I only finished half, and she gave me a C. And you have to go in to school tomorrow, but I really did it, honest, just forgot the notebook, that’s all. And I promise to fix the C, I mean, I’ll…” And he’s like: “Come on, you little slacker, let’s go home.”

—…screaming. And it’s always the same dream: his mama’s slapping him in the face and asking: “Did you eat the chocolate?!” He’s bawling and saying: “No!” Mama slaps him: “Did you eat the chocolate?!” Him: “No!” Mama slaps him: “Did you eat the chocolate?!” Here he breaks down and screams: “YES! YES!” And his mama bitch slaps him, screaming: “What did I tell you—never admit to anything!!!” Isn’t that horrible? For like six months I couldn’t get him to tell me anything about this nightmare of his, he would just be like: aw, what nightmare, everything’s fine.

—…when he loved me I was never jealous, but when he didn’t love me—I got jealous. I started calling him, driving both of us up the wall, until one time they had to call an ambulance for me.

—…I belong to this one rich man and I have to sing whenever he says. Because if I do it for one more year, then our group can get some decent money together and really get somewhere. But he’s totally unreasonable, he doesn’t try to be understanding, he doesn’t care—you can be sick, tired, have problems—go sing. Vera went to her sister’s wedd

ing, and he fired her. But I know what has to be done, because otherwise there’s no way we’ll get anywhere, it’s tough out there. So I put up with it. This one time he and his friends were having a cookout somewhere, he calls me—come over and sing. This is outdoors, and it’s September already. I get there and he gives me this huge coat, I mean, like a barrel. And I felt so gross singing in that coat, like crying, I mean really. I explain to him that you’re not supposed to sing when it’s cold out, singing is all about breathing, if I breathe normally out in the cold air then tomorrow my vocal cords’ll be shot, and if I don’t breathe, I’ll be singing using only my vocal cords and blow them out anyway. This is all going on at his dacha, it’s huge, pheasants, peacocks, dogs. And a silent pregnant wife following him around. And I’m thinking, this is probably a good match, she’s living well, but her life must be awful is what I think. “No,” he says, “sing.” I’d have quit a long time ago, but our group can’t get anywhere without his money and I want to get somewhere. But I’d still have quit a long time ago, only he comes to me after we’re done singing, sits down and cries. No, he hasn’t touched me, why the fuck do you keep asking me this bullshit, huh?!

—…every Christmas people set up those little scenes from the life of, you know, Jesus, little cradles and all that. So he bought like five pounds of meat and went around his neighborhood that night and switched out all the Jesuses with, like, hams…It was super conceptual, really great. Not like just sitting at home with the family, smiling like dumbasses.

—…a day. I spent the whole morning trying to write the screenplay, but I just kept coming up with cheap melodrama. Because real life just doesn’t produce tragedies of that magnitude. Either everybody dies, or, you know. Some kind of inexpressible spiritual torment. So I go out to pick up my suit and the whole time I’m in the subway I’m thinking: is this really OK? Because art is all about being able to see greatness in small things. The drama, you know, in simple things. And the more I think about it, like, the worse I feel. And suddenly at the Lubyanka stop I decide: aw, screw it, screw the suit. I’m going to get out right now, walk to The Captains and just get a drink. OK. I get out, and upstairs I get three texts in one go. From three different people, obviously. “I’m in the loony bin, they’re keeping me here for now”; “Anya died yesterday. I’m not flying in”; “Dad’s crying and begging for me to take him home.” I read them once, a second time, a third, and suddenly I realize I’ve been looking at my phone and walking in circles around the lamppost for fifteen minutes.

—…And when my daughter accidentally crushed the hamster in the door, he cried. He kept saying: “He was a great guy!”

—…I’m walking around shaking. The place was already full of people, super crowded, everyone’s coming up, like: “Oh dude, so cool!” and all that, but I’m still scared shitless. I’m walking around behind everyone’s back so I can see who’s looking at what. I mean, on the one hand it’s not OK to walk up real close to people, ’cause you really can’t eavesdrop at your own show, but, you know: at least you keep an eye on who stops in front of what, you know, how they look at it. So I walk behind this one column in the gallery, near where that dude of mine is standing, you know, the one with the spindly legs. And I see Tultsev himself standing in front of him with his notepad. I’m all: “Jackpot.” And my heart goes: “Boom!” I stand there real quiet and watch. And he’s there, looking at my dude, and, like, super focused. I’m like: “No way.” And he stands there for like three minutes, looking, or five. And he even, like, I mean, he starts to smile a little bit. He’s standing there looking and smiling, I mean, well, like a person who’s feeling just fine. And I’m all: “Ahhhh!” So then at some point he walks away. I think: why don’t I stand there too and have a look at my fan-fucking-tastic sculpture. And I stand right on the same spot where he was standing. Fuuuuuuck!!! There, right behind my dude, I mean, a little to the left, there’s a cat cleaning itself. Licking, and licking, and licking…

—…I ask: “Mama, what do you want for New Year’s?” And you know what she says, the old bag? “Don’t buy me anything, sonny, who knows if I’ll even make it till then…”

—…we’re at the end of our rope, fighting like cats and dogs. So then Milka tells me: go see the priest. I come in and I’m like: “Father, I just can’t do it, it’s horrible, I’m ready to throw him out. He’s my husband, after all, but the way we live, I’m ashamed in front of my own kids!” He asks me right away: “Do you have an altar in the house?” Well, no—I say—we don’t. “Then how,” he says, “how can you want there to be room for your husband in the house if you don’t have room for God? You should go,” he says, “right now”—and he told me where to go and what to buy: you know, that little shelf for the icon, something to put under it, and a candle, holy water too. And he told me how to do everything, how to pray, where to hang it, and with the water, I mean, everything. I hauled over there after work, I was totally beat, came home…What can I say, I hung it all myself, set it all up, and what do you call it, sprinkled it all with the water. And I did the bows and said everything I had bottled up inside—that he’s my husband but there are times I could really kill him, like, it’s enough to see him and I’m ready to kill him, and help me Lord, and all that. And you know, somehow I felt…better, and I’m already thinking—well, OK, maybe with God’s help we can start living like human beings. I turned around—and he’s standing there. I say to him: “What do you want?” And he’s looking at me and says: “Zina…But there’s no God…”

—“…all my life I wanted to become a real grown-up lady that all the little girls would talk about, saying: ‘Wow, what a cool dollhouse she has!’”

—…everyone hates us, but it’s not like we’re having a great time. Like, on New Year’s the boys call me up: lieutenant, sir, they say, there’s a guy climbing the Christmas tree here. You know, near Lubyanka, on that street, Nikolskaya. He’s climbing right up like a monkey. And it’s a holiday. And I think: so now I tell them to take him down and bring him in, and it’ll just be one more police asshole sticking it to someone, on New Year’s to boot. So I’m like: “Is he climbing kinda calmly?” They say, “Yeah, pretty calmly, just climbing along.” “Then screw him,” I say, “let him climb.” The boys don’t care, it’s a holiday for them too, they want to do like everybody else. So I’m sitting there thinking: I did a good deed, like they say—how you start off the year and all. So I’ll have a good year. Then fifteen minutes later they call again. He crashed down out of that tree and broke his neck. Soon as they got to him he’d already broken it. There’s your good start. And you tell me everyone hates us! Why don’t you climb on down here with your ID ready, don’t fuck with me, you smartass!”

—…I’m straight up beating myself on the chest and begging her: “Lusia, I swear, never again in my whole life! I won’t even look at any other woman! I won’t even look, just forgive me! So then she’s like: “Swear it.” And I’m like: “I swear.” And she says: “Wait, no, not like that. Swear on your mother’s life.” “Aww, Lusia,” I say, “not that. If anything happens to my mother, you’ll be like: ‘Aha! You’ve been out with her again!!!’”

—…at two in the morning some kind of angel flew in. Totally drunk; he was hanging there outside the window, refusing to fly over the windowsill. Kept calling me Natalya. Sobbed, kissed my hands, said that he’d sunk so low, couldn’t get any lower. Kept asking if he could still be saved. I said sure, didn’t want to upset him.

—…I always loved my wife, loved her like you can’t even imagine. But she—well, it seemed to me anyway—she thought I was just OK. My mother says to me: “Get a lover. Your wife’ll love you more.” I started seeing this one woman. I mean, I didn’t love her, of course. I loved my wife, didn’t love this one. But I would go see her. Then I thought: my wife needs to find out. But I can’t tell her. She’s why I started the whole thing, but I can’t tell her. My mother says: “Tell the kids, they’ll make sure she finds out.” My kids, like I told y

ou, I’ve got two sons, one of them had just started college then, and the younger one was fifteen. I called them over, I got home and sat them down, I say: “Boys, listen to me. I’m going to tell you something terrible, I hope you can forgive me. Boys, I have another woman in my life besides your mother.” And I don’t say anything else. They looked at each other and all of a sudden just crack up! And the younger one slaps me on the shoulder and says: “Good work, dad!” And the older one says: “Cool. We won’t rat you out.” So to this day I’m still seeing that broad. Goddamn.

Found Life

Found Life